Algebraic Geometry

孙晟昊 shsun@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn

- 答疑:Fri 9-10 am, online

- HW (40%) + Final (60%)

References

- Harris, GTM133

- Shafarevich, Basic AG, Vol I

- Mumford, AG I: Complex Proj. Var.

- Hartshorne, GTM52, Chap I.

Preliminaries

Constructions from rings

Finitely generated: f.g. $\newcommand{\aqty}[1]{\left\langle#1\right\rangle}$

-

f.g. $A$-module: $A\aqty{\alpha_1,\cdots,\alpha_n}$, linear combinations with coefficients in $A$.

-

f.g. $A$-algebra: $A[\alpha_1,\cdots,\alpha_n]$, polynomials over $A$.

-

f.g. field extension $L/K$: $L = K(\alpha_1,\cdots,\alpha_n)$: fraction of poly’s $P(\cdots)/Q(\cdots)$.

Integral element

$A\subset B$ rings, $b \in B$ integral over $A$:

\[b^n + a_1 b^{n-1} + \cdots + a_n = 0 \quad\text{in $B$,}\quad a_i \in A \label{eq:integralElement}\]i.e. $b$ is a root of some monic ($a_0 = 1$) poly. over $A$.

e.g. $\sqrt{2}\in\mathbb{R}$ integral over $\mathbb{Z}$: $(\sqrt{2})^2 - 2 = 0$.

Idea: We are extending $A$ with roots of its poly’s. Wiki: If $A, B$ are fields, then the notions of “integral over” and of an “integral extension” are precisely “algebraic over” and “algebraic extensions” in field theory (since the root of any polynomial is the root of a monic polynomial).

Lem. $A\subset B$ integral domain (整环), $b \in B$ integral over $A$

$\Longleftrightarrow$ $b\cdot W \subset W$, for some fintely generated (f.g.) non-zero sub-$A$-module $W\in B$.

Pf.

-

$\Longrightarrow$: Take $W = A[b] = A\aqty{1,b,b^2,\cdots,b^{n-1}}$, $b^n$ can be reduced using \eqref{eq:integralElement}.

-

$\Longleftarrow$: $b\cdot W \subset W$ implies that:

\[\sum_j \pqty{ b\,\delta_{ij} - a_{ij} }\,b_j = 0, \quad \det \pqty{ b\,\delta_{ij} - a_{ij} } = 0\]The determinant is a poly. in the form of \eqref{eq:integralElement}. Here $b_j$’s are the generators: $W = A\aqty{b_1, b_2, \cdots, b_n} \subset B$.

Prop. $A\subset B$ int. dom., $b,c\in B$ int. elements, then so is $(b+c)$, or $(b\cdot c)$.

Pf. Use Lem.; construct $W = A[b,c]$.

Comment: This is non-trivial! Consider finding the minimal poly. of $\sqrt{2} + \sqrt[3]{5} + i$ over $\mathbb{Q}$. Prop. in fact gives an upper limit of the poly. deg.

Thm. (Hilbert’s Nullstellensatz — zero-locus-theorem, algebraic version)

If:

- $L/k$ field ext., also!

- $L$ is a f.g. $k$-alg. as well, $L = k[\alpha_1,\cdots,\alpha_n]$.

i.e. $ L = k[\alpha_1,\cdots,\alpha_n] = k(\alpha_1,\cdots,\alpha_n) $.

Then $L/k$ is an algebraic & finite ext.

Concepts: field ext.

- algebraic: all elements are roots, e.g. $\mathbb{C}/\mathbb{R}$.

- transcendental: non-roots, e.g. $\mathbb{R}/\mathbb{Q}$.

All transcendental exts are of $\infty$ deg. Hence all finite exts are algebraic. But

Pf.

-

It suffices to show that each $\alpha_i$ is alg. over $k$.

-

Induction on $n$ (the number of generators).

-

By contradiction: for $\alpha = T$ transcendental, consider $A = k[T, \tfrac{1}{f(T)}] \subset k(T)$ — this is called localization: by manually adding inverses, the domain is restricted / localized around “non-zero” regions.

-

We can check that $A$ is a field;

-

However, $A$ is not a field, since there are $\infty$-ly many irreducible poly. in $k[T]$, which can be shown using Euclid’s arguments, similar to the proof that there are $\infty$-ly many primes.

-

Intro

Geometry: $X$, $\mathbb{R}$-algebra:

\[\mathbb{R} \longrightarrow C(X) = \Bqty{\, f\colon X\to\mathbb{R} \,}\]- $X$: Top., $C^0(X)$

- $X$: Diff., $C^\infty(X)$

- $X$: complex, $\mathcal{H}(X)$

- $X$: alg. variety, $\mathcal{O}(X)$: polynomials on $X$.

Consider a surjective $\mathbb{R}$-algebra hom.

\[\mop{ev}_x\colon \ C(X) \longto \mathbb{R},\quad f\longmapsto f(x)\]$m_x\subset C(X)$ a maximal ideal: $ m_x = {f \,|\, f(x) = 0} $. We have thus represented a pt. with an algebraic object.

Note: the kernel of ring hom. is an ideal, just like the kernel of group hom. is a normal subgroup. If we quotient out the ideal (or normal subgroup), then the isom. descends to an isom. to the image. These are the so-called isomorphism theorems.

Furthermore, for commutative rings, if the image is a field, then the kernel (ideal) is maximal.

If $X$ compact Hausdorff, we have a bijection:

\[\mop{ev}\colon \ X \longto \Hom_{\mathbb{R}-alg.} \pqty{ C(X),\mathbb{R} }, \quad x\longmapsto \mop{ev}_x\]Moral: Recover geometry $X$ from algebra hom’s.

\[\mop{Specm}\big(C(X)\big) = \Big\{ \text{all max ideals in $C(X)$} \Big\}\]To study geometry, we can consider various structs:

- $S^7$, $\mathbb{R}^4$ diffeo structs

- Torus complex structs

For $(x,y) \in \mathbb{C}$, consider:

\[y^2 = x^3 + 1 \quad\text{vs}\quad y^2 = x^3 - x\]diffeo, but not biholomorphic (neither isom. as $\mathbb{C}$-alg. varieties).

Affine Space

Field $k = \bar{k}$ (assume algebraic closed for simplicity); affine space: $\mathbb{A}_k^n$. As a set, $ \mathbb{A}_k^n = k^n $; however we’d like to allow all poly. functions:

\[f\colon\ k^n \to k,\quad \forall\ f(T) \in k\bqty{ T_1,\cdots,T_n } =\colon A\]Idea. Define geometry (alg. var.) from the allowed functions; recover $\mathbb{A}_k^n$ from poly. ring $A$. Similarly, we use $\mop{ev}_a$;

\[m_a = \ker (\mop{ev}_a) = \Bqty{ f\in A \,|\, f(a) = 0 }\]In fact, any max ideal $m\subset A$ takes the form:

\[m = \pqty{ T_1 - a_1,\cdots,T_n-a_n } = \ker(\mop{ev}_a) = m_a\]Why? Think of Taylor expansion around the root $a$. The proof of this follows from Nullstellensatz: $A/m$ is a field, and a f.g. $k$-alg., therefore it is a finite extension of $k$; but $k = \bar{k}$ so $A/m = k$.

Affine (sub)varieties: solution set of a system of poly. equations.

However, this is a redundant description since many systems can lead to the same solution set. How to remove such redundancies? Use the ideal $I\subset A$ generated by the system of eqns. This gives the common zero locus:

\[X = Z(I)\subset \mathbb{A}^n,\quad Z(I) = \Bqty{ a\in\mathbb{A}^n \,|\, f(a) = 0,\ \forall\ f\in I }\]Similarly, we have $1:1$ identifications:

- pts. in $Z(I)$

- $k$-alg. hom. $A/I \to k$, i.e. $\Hom_{k-\mathrm{alg.}}(A/I,k)$.

- max ideal $m\subset A/I$, or equivalently $I\subset m \subset A$. This one relies on $k = \bar{k}$ and the Nullstellensatz.

Conversely, given some arbitrary $X\subset \mathbb{A}^n$, def. its ideal:

\[I(X) = \Bqty{ f\in A \,\Big|\, f|_X \equiv 0 }\]We can then define the affine coord. ring with $f \equiv g\ \mop{mod}\, I(X)$:

\[k[X] \mathbin{:=} A/I(X)\]It is illuminating to go back and forth: $I \to X = Z(I) \to I(X)$, and see if $I \overset{?}{=} I(X)$. In fact, we have:

-

$I(X) \supset I$; e.g. for $I = (T^2) \subset k[T]$, we have $X = Z(I) = {a = 0}$, $I(X) = (T) \supsetneq I$. However, in this case we do have this funny result:

\[\sqrt{I} = \sqrt{(T^2)} = (T) = I(X)\]We are taking the “square root” of $I$; this can be formalized as the radical of $I$: $\mop{rad} I \equiv \sqrt{I}$.

- $I(X) = \sqrt{I(X)}$: always radical — $f^N(a) = 0\ \To\ f(a) = 0$, a field does not contain nilpotent element.

-

In fact, for $k = \bar{k}$, we always have $I(X) = \sqrt{I}$. This is the Geometric Nullstellensatz. This leads to the fact that:

\[\Hom_{k-\mathrm{alg.}}(A/I,k) \cong \Hom_{k-\mathrm{alg.}}(k[X],k),\quad k[X] = A/I(X)\]i.e. $A/I\to k$ always descends through $A/I(X) = k[X]$:

\[A/I \longto A/I(X) \longto k\]

Localization

Idea. By adding allowed functions, we shrink the space (removing pts on which the functions cannot be defined).

- $\mathbb{A}^1_k \leadsto k[T]$

- $\mathbb{A}^1_k - {0} \leadsto k[T, \tfrac{1}{T}]$

- $\mathbb{A}^1_k - {0,1} \leadsto k[T, \tfrac{1}{T}, \tfrac{1}{T-1}] = k[T, \frac{1}{T(T-1)}]$

Notation: $S = (f) \subset A$ some subset closed under multiplication, we can define $S^{-1} A = A[\frac{1}{f}]$. Furthermore, if $S = A - p$, where $p$: some prime ideal, then we denote:

\[A_p \mathbin{:=} S^{-1} A\]With this notation, we can write down the algebraic description of “a small neighborhood around $0\in \mathbb{A}^1_k$” — in this case we want to remove (almost) every point except the origin, i.e.

\[\Bqty{ \frac{f(T)}{g(T)} \,\bigg|\, g(0) \ne 0,\ \text{or}\ g(T) \notin (T) } = S^{-1} k[T] = k[T]_{(T)}, \\ p = (T),\quad S = k[T] - p\]Tangent Space

e.g. Plane curve $C = Z(f) \subset \mathbb{A}^2$, tangent line $T_x(C)$? For intrinsic def, use derivation which satisfies the Leibnitz’s rule:

\[\pd\colon\ C^\infty(X) \to k,\quad\]However, $C^\infty$ might be too much: e.g. $\mathbb{C}$ mfd is very rigid; for compact $\mathbb{C}$ mfd, global holomorphic functions are always constant (by maximum modulus principle); i.e. topology of the mfd is a very strong constraint (too strong than what we’d like). Therefore, we shall consider “locally holomorphic” functions.

For plane curves defined by $f = 0$, locally defined polynomials can be neatly written down with the help of localization:

\[\Big( A/(f) \Big)_{m_p},\quad m_p = (x_1 - p_1, \cdots, x_n - p_n)\]We shall then consider the following derivations which spans $\mathrm{T}_p C$:

\[\pd\colon \Big( A/(f) \Big)_{m_p} \longto k,\]Before continuing, let us first consider $A_{m_p}$ without restricting to the curve, or equivalently, taking $f \mathbin{:=} 0$. e.g. $ T_{p=0}(\mathbb{R}^n) = \mathbb{R}\aqty{ \pdv{}{T_1},\cdots,\pdv{}{T_n} } = \Bqty{ v^i \pdv{}{T_i} } \cong \mbb{R}^n $. $\pd$-action on $A_{m_0}$ is induced from its action on $A$, and is completely fixed by the Leibnitz’s rule. e.g. $\pd\,(1) = \pd\,(1\cdot 1) = 2\,\pd\,(1) = 0$, etc. We have:

\[T_0 \mathbb{A}^n = \Bqty{ \pd\colon A_{m_0} \to k } \cong \Bqty{ \pd\colon A \to k } \cong k^n \label{eq:tangent_derivation_vector}\]Rmk. We see that there is no need for localization (to a point $p$) to define the tangent space on a $\mathbb{R}$-mfd; why? We have partition of 1 (unity) for a $\mathbb{R}$-mfd, so that local functions can always be stitched together to make a global function. This is not true for $\mathbb{C}$-mfds.

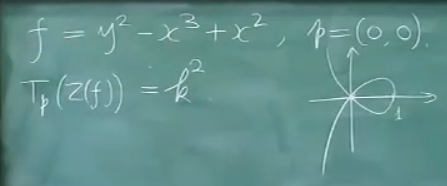

Back to the curve $C\colon f = 0$, we have:

\[A \longto A_{m_p} \longto A_{m_p} / (f) \cong \Big( A/(f) \Big)_{m_p}\]Note that localization commutes with the quotient. $\pd$ on $\Big( A/(f) \Big)_{m_p}$ is contrained by the quotient: $\pd f = 0$. By \eqref{eq:tangent_derivation_vector}, we have:

\[T_p C \cong \Bqty{ v\in k^2 \,\bigg|\, \pd_v f = v^i \pdv{f}{x^i} = 0 }\]Note that:

- smooth pt $\leadsto$ $T_p C$: a tangent line (tangent);

- singular pt $\leadsto$ $T_p C \cong k^2$: the whole plane, $\pdv{f}{x} = \pdv{f}{y} = 0$.

e.g.

e.g (affine) twisted cubic curve: $(t,t^2,t^3)$, or

\[I = \{f \,\big|\, f(t,t^2,t^3) = 0\} = (y - x^2, z - x^3) = (y - x^2, z - xy)\]Zariski Top.

Def. closed sets are $Z(I),\ I \subset A$ ideals; $Z(0) = \mathbb{A}^n,\ Z(1) = \varnothing$.

-

$Z(I_1) \cup Z(I_2) = Z(I_1 I_2)$, by the property of prime ideals (if $f_1f_2 \in I$, then $f_1\in I$ or $f_2\in I$; max ideals are always prime for comm. rings); or think of products of equations;

-

$\bigcap_i Z(I_i) = Z\pqty{\sum_i I_i}$, think of a system of equations;

e.g. closed subsets in $\mathbb{A}^1$ are finite pts and $\mathbb{A}^1$ itself (余有限拓扑). Note that open sets are very large in such topology, hence this is a very coarse topology.

There is a natural top. basis: $U_f = \mathbb{A}^n - Z(f),\ \forall\ f\in A$. By definition, any open set can be written as:

\[\mathbb{A}^n - Z(I) = \mathbb{A}^n - \bigcap_{f\in I} Z(f) = \bigcup_{f\in I} \big( \mathbb{A}^n - Z(f) \big) = \bigcup_{f\in I} U_f\]Note that $f\in A$ irreducible poly. $\To$ $(f) \subset A$ prime ideal; this motivates us to define that:

Def. irreducible set (algebraic): $X$ irreducible if $I(X) \subset A$ prime ideal. This is related to the geometric (topological) notion of irreducibility:

Prop. irreducible set (geometric): $X$ irreducible iff $X \ne Z(I_1) \cup Z(I_2)$, i.e. $X$ can not be decomposed into two proper closed sets.

In the spirit of localization, we can def. (local) regular functions:

\[\mcal{O}(X) = \Bqty{ f \,\bigg|\, \forall\ p\in X, \ \exists\ U_p \subset X, \ \text{s.t.} \ f\big|_{U_p} = \frac{g}{h}, \ h\big|_{U_p} \ne 0 }\]e.g.

- $\frac{1}{T}$ regular on $\mathbb{A}^1 - {0}$

- $\frac{1}{T^2 + 1}$ regular on $\mathbb{A}^1_{\mathbb{R}}$

Rmk. a different perspective: a resolution without localization is to start with function fields on $X$, e.g. meromorphic functions on a $\mathbb{C}$-mfd.

Consider:

\[k[X] \mathbin{:=} A/I(X) \hookrightarrow \mathcal{O}(X)\]Q. Surjection?

LHS: some poly.’s, nonzero on $X$; RHS: locally-defined fractions. This is clearly not true, for $X$: arbitrary set, e.g. $X = \mathbb{A}^1 - {0}$. However, what if:

- $X = Z(I)$: a alg. var., or equivalently,

- $X$ closed in $\mathbb{A}_k$

This is still not true if $k \ne \bar{k}$, e.g. for $k = \mathbb{R}$ we have $\frac{1}{T^2 + 1} \in \mathcal{O}(x)$.

Surprisingly, if $k = \bar{k}$, we do have $A/I(X) \cong \mathcal{O}(X)$, i.e. local fractions are all restrictions of global poly’s. In fact, we have:

-

pt-wise: $\mathbb{A} \cong \mop{Specm} A$, or

\[\Big\{ a\in \mathbb{A} \Big\} \longleftrightarrow \Big\{ \text{max. ideals} \ m_a \subset A \Big\}\] -

Affine varieties:

\[\Big\{ X = Z(I) \subset \mathbb{A}^n_k \Big\} \longleftrightarrow \Big\{ \text{rad. ideals} \ I \subset A \Big\}\]

It is easy to check that:

\[X = Z(I)\mapsto I(X)\mapsto Z(I(X))\]is an identity map, since $I(X) \supset I$, $X\subset Z(I(X)) \subset Z(I) = X$. What about the other way around? i.e.

\[I = \sqrt{I} \mapsto Z(I) =\colon X \mapsto I(X) = I(Z(I))\]This is non-trivial, and due to the Nullstellensatz.

Geometric Nullstellensatz

\[I\pqty{Z(I)} = \sqrt{I}\]Obvious: $I\pqty{Z(I)} \supset \sqrt{I}$.

Special case: $Z(I) = \varnothing\ \To\ I = A$. Otherwise, by alg. Nullstellensatz there is some max ideal $m$ s.t. $I \subset m \subset A$, and $Z(I) \supset Z(m) = {a} \ne \varnothing$.

General case: reduced to special case! For $f\in I(Z(I))$, consider “embedding” into higher dimensional space: $A \hookrightarrow A’ = k[T_1,\cdots,T_n,T_{n+1}]$, then we can construct:

\[J = I\cdot A' + \Big( T_{n+1} f(T_1,\cdots,T_n) - 1 \Big)\]Clearly $Z(J) = \varnothing$, thus by the special case $J = A’$.

This is the trick of Rabinowitsch. Intuitively, we embed $Z(I)\hookrightarrow Z(I)\times \mathbb{A}^1$, but then “removes” $Z(I)$ (and possibly more) by imposing a “parabolic” constraint: $T_{n+1} f(T_1,\cdots,T_n) = 1$. The resulting $Z(J)$ is clearly empty. This is localization in disguise!

\[A'/(T_{n+1}f - 1) = A[\tfrac{1}{f}]\]Now we have $A’/J = 0 = A[\tfrac{1}{f}] / (I\cdot A[\tfrac{1}{f}])$, i.e. $1 = \sum a_i b_i \in A[\tfrac{1}{f}]$. Equivalently,

\[f^N = \sum a_i b'_i \in I \subset A\]Thus $f\in \sqrt{I}$. $\ \blacksquare$